Over spring break, my mom and I visited England and Scotland for the first time. Despite having Scottish roots, the only place I had been to previously in Europe was Italy because I have a lot of family over there.

Since it was just the two of us, and I love history, we decided to spend the majority of our trip exploring castles and manors. Sadly, I can’t talk about every place because this story would be like 70 pages long. So I’m only going to focus on my absolute favorite: Chatsworth House.

This is, without a doubt, my favorite place we visited. The original reason we went was because it is where they filmed “Pride & Prejudice (2005), and if you should know anything about me, it is that “Pride & Prejudice” practically runs through my blood.

I had a very strong, slightly weird obsession with the book from fourth to sixth grade. I would, quite literally, read the book once a month and watch the movie almost every other Saturday (it started off as every Saturday, but I was worried I would become sick of it).

Once I even re-enacted the movie, by heart, for my parents with a cardboard version of Mr. Darcy I had made, and I’m not even joking. Focusing back on Chatsworth, even though I came for “Pride & Prejudice,” the experience I had there far surpassed that.

Chatsworth House has seasonal exhibitions, and I was lucky enough to visit during “The Gorgeous Nothings: Flowers at Chatsworth,” which is open until October 5. As the name suggests, every piece of artwork was related to flowers in all their forms and incarnations.

This idea stemmed (not a pun, I swear) from the Library at Chatsworth. The Library has always had an extensive collection of botanical books, even containing the first ever book to be illustrated with photographs.

“The Gorgeous Nothings” was dedicated to flowers, horticulture, and the relationship that plants have with the house, garden, and its contents. The artworks range from new voices and perspectives to pieces from private collections. It also includes an important lineage that the gardeners have formed at Chatsworth, with conserved and protected specimens from over the past five centuries.

Botany is often referred to as the science of beauty, but I believe the exhibit also shows a study of humanity. It encompasses a series of themes that express the features and temperatures of flowers, and by association, human nature in all of its contrast and complexities: mythology and magic, still life, gatherers, in place and out of place, sexuality and the senses, beauty and horror, permanence and transience, and flowers as symbols. I’m going to pick out a few of my favorite pieces and cover them to the best of my ability.

Mythology and Magic

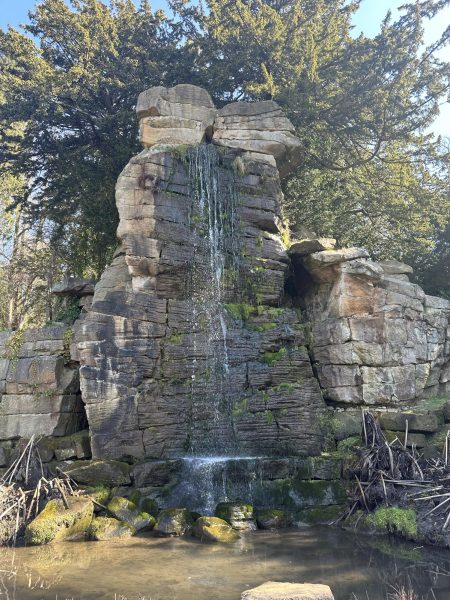

Historically, flowers have had an impact on the mythological world and tales of the supernatural. The room, the Grotto, allows flowers to embody the otherworld through works of the past and present.

Diana (the Greek goddess of wildlife and the moon) is showcased in the first artwork that catches your eye when you walk in. She is captured bathing, surrounded by her nymphs and sea creatures in an ornate 17th-century fountain. As the benefactress of nature and birth, she almost serves as a talisman in Chatsworth.

Grottoes themselves have long been described as portals to the underworld and places where the divine dwell. So they are places of protection and seclusion, yet somehow are never safe. They hold the constant fear of the underworld. There is a similar atmosphere amongst the other artworks in the Grotto. For example, the Lost Valley Mirror. The mirror was made in 2019 by David Wiseman, and it captures the lure and mystery of the Grotto. Its slightly jagged appearance and ornaments of forest wildlife encompass the bewitching nature of the room.

The Grotto also contains one of my personal favorites from the entirety of the house: a bronze copy of Schwanthaler’s Shield of Hercules. I don’t have a particular reason for liking it, nor do I think it held some kind of purpose (I suppose it could be something with protection since it is near Diana). I just really liked it. In the center of the bronze shield, there’s a small gold dragon roaring that drew me in. Surrounding the dragon, there is war and peace coexisting. It was a really great way to leave the room.

Gatherers

Gathering–to bring together and take from different places and sources– is an act of preservation and often survival. This practice is ingrained in the history of Chatsworth through centuries of foraging, researching, assembling, and preserving.

Like the manor, the artists featured in this exhibition are all gatherers of sorts: they explore nature and science, and transform specimens into formats from their own imaginations.

My personal favorite piece from “Gatherers” is the first ever book–of any subject–to be fully illustrated with photographs. I was staring at it and trying to imagine what this would have looked like in the 19th century.

I was especially interested to learn that this book was created by a woman working in botany, an extremely male-oriented practice at the time. There are many interesting artworks in the gallery but I found myself wandering back over to the revolutionary book.

Beauty and Horror

It is immediately obvious that this theme is different upon arrival. It’s the only completely modernized room in the house. Even the gift shop walls were adorned with styles of the 19th century, but this room is completely yellow.

The walls from head to toe, the stands, and the descriptions were all yellow. The only thing that is different is the preserved plants atop the stands. The world of plants stands in a field of yellow. It’s meant to be contradictory, I believe.

This room, like plants, was opposite to everything else. Where there is growth, there is decay, where there is science, there is serendipity, and where there is beauty, there is horror. This is similar to the contrasts of human nature.

This theme only has one exhibit, “The Marias.” Reconstructions of flowers by the 17th-century botanist Maria Sibylla Merian point to the persecution of women during colonialism.

The peacock flower (one of the main flowers in the room) can act as a natural way to terminate pregnancy; this was a method used by many women to maintain control of their bodies and break the chain of exploitation.

I think the yellow surrounding these flowers is meant to be the sun. The color evokes the harsh light of sun-rays, while vividly foregrounding the horrors of the past.

Permanence and Transience

This was actually one of my favorite sections of Chatsworth. It was slightly gloomy compared to the rest of the manor, but I think it just made the art pop out. It is located amongst the infamous Library, which, fun fact, Ernest Hemingway would read at.

The theme focuses on Surrealist art and the Japanese art form of Ikebana. The term “Ikebana” comes from the combination of “ikeru”(to arrange, have life, be living) and “hana”(flower). It is most commonly related to nurturing, arranging, and viewing plants throughout all seasons, as established in Japan 550 years ago.

Alessandro Piangiamore blends life and death in his own interpretation of the art. He used flowers found on the streets and markets of Rome and impressed the flowers in poured concrete.

His art brings gravity and solidity to the Japanese art form. So seeing his pieces near the books was shocking. I just found it hard to believe that something so beautiful could be made from the thrown-away scraps of others.

A Flower is a Symbol

For centuries, flowers have been incorporated into the visual arts. They almost always appear as attributes of the subjects they accompany, as evocations of status and origin, or as premonitions of the future.

A rose, for example, can have a very different meaning depending on the context it is depicted in. In Christian iconography, it is the flower of martyrs and miracles. It emphasizes beauty and purity, but in Domenichino’s “Madonna della Rosa,” it also alludes to thorns and impending death. Roses can also symbolize fidelity, softness, and most commonly, love. But it can also warn us of the dangers of love.

I like to think that the installations presented at Chatsworth are to invoke tenacity and focus on “gatherers.” Also, they reflect the resilience and persistence of nature amidst the environmental crises. Each flower shown is associated with deep-rooted and geographically diverse histories and myths. Individually, flowers might be considered gorgeous nothings, but together they manifest life and endurance against all odds.