Ban Our Books, Ban Our History

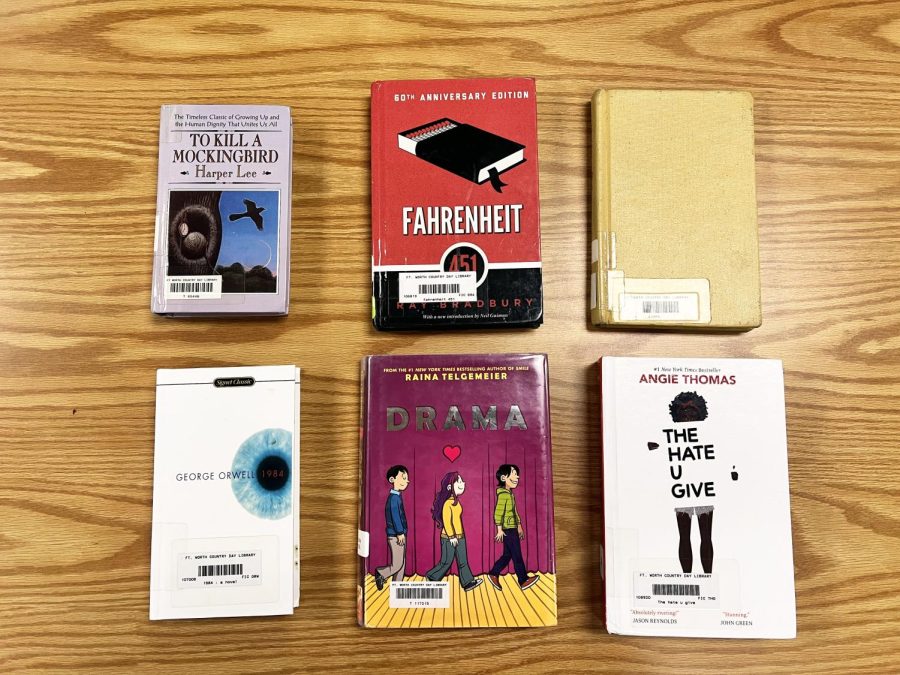

The Moncrief Library has a variety of commonly banned or challenged books.

May 6, 2022

Right now in the United States, countless books are being banned from schools’ libraries and curriculums, and Texas schools have notably been at the forefront, having banned and challenged dozens of books so far.

In the past ten years, it has been rare for a school to have banned a book, and on the national level, there has not been a book banned since 2010, when the U.S. The Department of Defense physically destroyed around 10,000 copies during “Operation Dark Heart,” and censored over 200 sections of the remaining copies over national security concerns.

However, since the pandemic, there has been an enormous increase in the push to ban certain books at both the state and school district levels. Unlike before, the concerns are not exactly fears that there had been a breach in national security.

“The pandemic is a stressful time, and when we are under severe stress, we tend to cling much more tightly to our core beliefs and to the exclusion of other ideas,” US English teacher Laura Hayes said. “It’s like, we’re so stressed, we just have to hang on to what we know.”

In November 2021, Representative Matt Krause, who represents parts of Fort Worth and Tarrant County in the Texas House of Representatives, compiled a 16-page list of over 800 books that he deemed inappropriate for schools. He then sent the list to school districts across Texas.

“I took a look at that,” FWCD Head Librarian, Tammy Wolford, said. “I really wondered who created that list because sometimes the Spanish version of the book was on there – but not the English version – or there might have been a medical book, something that wouldn’t have been in a school library anyway.”

In a statement, Fort Worth Independent School District Superintendent Kent Scribner stated that FWISD would comply with the letter and report back to Krause with information regarding whether they have these books and how much money had been spent on them.

After three weeks of FWISD librarians searching for the titles, it was found that out of the 864 on Krause’s list, only 21 were not available in FWISD libraries. The majority of the books were available in only one library. No community member in the district has challenged a book on the list since the letter became public, and in FWISD’s history, there has never been a banned book.

“My co-librarian and I select books through a rigorous process,” Paschal High School Librarian, Jennifer Dean, said. “Banning books certainly does strike fear into me. Any time we ban a book based on certain criteria, we are telling a student who might relate to that book that whatever they may see inside that book – that represents them – does not matter.”

At FWCD, like most other libraries, there is a reconsideration policy, meaning that when a book is challenged by a member of the community, a formal document is filled out regarding the concerns of content. Once that request is filled out, the book is reviewed by a committee of faculty and teachers, to judge a book on its merits.

After a decision is made about a challenged book, it is either kept on the shelf for students to check out or put behind the desk so students can request to check it out. There is yet to be an occasion where there has had to be a reconsideration committee meeting at Country Day.

The reasons that titles are being challenged vary greatly. Some cover the topic of anti-racism, such as “This Book is Anti-Racist,” challenged for “indoctrination,” and “The Hate U Give,” challenged for profanity.

Others cover coming of age, like “The Fault in Our Stars,” challenged for mortality, and “Drama,” a graphic novel challenged for featuring gay characters.

“We have students who have different identities, who have different voices, and [when books are banned] they don’t get [the opportunity] to engage with literature that reflects their identities and their needs – to provide a safe and comfortable place for them,” Hayes said. “When you take [that opportunity] away, you take away something that connects with them.”

Many of the most commonly challenged books are books that are in the Country Day curriculum. Titles including “Night,” “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and “Fahrenheit 451” have all been challenged and banned in schools. “Night” has been banned for violence and profanity; “To Kill a Mockingbird” for profanity and the topics of racism and rape; and “Fahrenheit 451” for graphic imagery and profanity.

“The books that we would consider some of the best books that everybody should read – like ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ – are being challenged. What it comes down to is that it’s really something that has offended someone’s value system,” Wolford said, “ So, just like in this, we teach it because our community has decided that ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ is something we value. ”

Many of the books’ themes are taken out of context when a book is being challenged.

“Good literature makes us uncomfortable. It’s only through being uncomfortable that we can evaluate and understand ourselves better,” Hayes said. “We can’t grow as human beings if we’re not made uncomfortable.”

While “Night” tells Elie Wiesel’s devastating experiences as he goes through Auschwitz, while “To Kill a Mockingbird” tells the story of the racism in a trial in 1930s Alabama, and while, ironically, “Fahrenheit 451” tells the story of a dystopia where havoc breaks loose after all books are burned, the purpose of these books is to show real-world issues in a different perspective, and these stories need to be told.

“Books allow us to see ourselves through a mirror but books also allow us a window into another world or another perspective,” Wolford said. “What books do is they help us create empathy: I don’t have to have a terrible experience, I don’t have to experience what this person has gone through because when I read a book about it, it becomes so real to me.”