Chemistry Department Discovers Old Chemicals

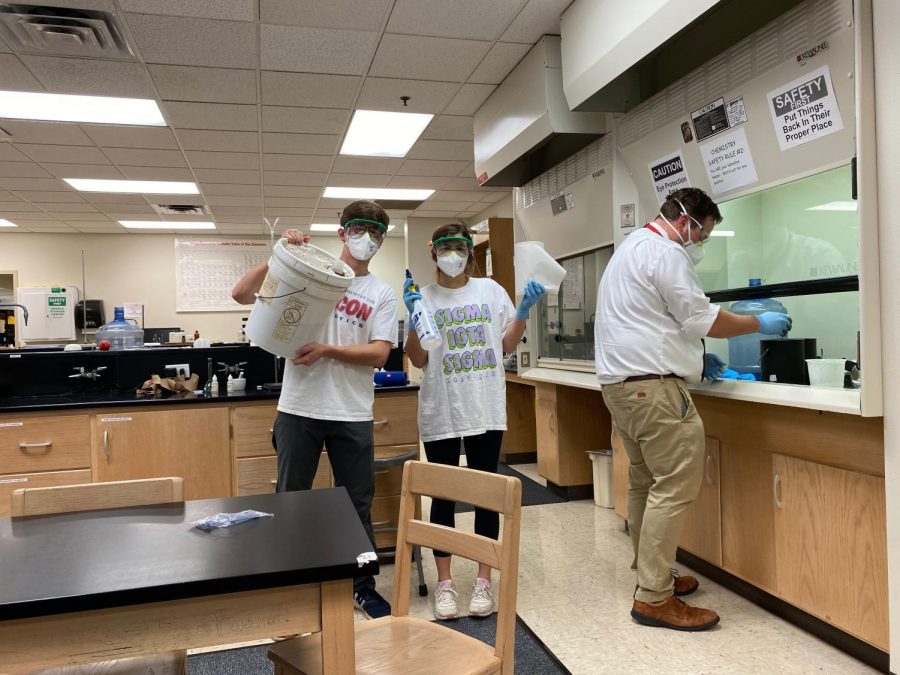

Gage Fowlkes ’22 and Jayne Dodson ’22 volunteer to work in the lab during their free time and weekends. Photo courtesy of Fowlkes

November 30, 2021

Wednesday, October 29, 2021.

For everyone else it seemed like a perfectly normal parent-teacher conference day.

However, to Jayne Dodson ‘22, Gage Fowlkes ‘22, and Mark Lichaj, US Science teacher, the day was anything but ordinary.

Since Dodson and Fowlkes are Lichaj’s lab assistants, they were at school on their off day to clean out the chemicals cabinet. Fowlkes looked in the organics cabinet and discovered old solvents and discolored Xylenes. Due to Fowlkes’s love for chemistry, he had read stories about labs blowing up because of old solvent bottles.

“It is important to note that the chemicals themselves aren’t dangerous,” Fowlkes said. “It’s what happens after they get too old.”

Certain solvents will absorb oxygen from the air and create long chains of solvent molecules and oxygen, making them explosive. The slightest movement of taking off the cap or shaking the bottle is enough to make the chemicals detonate if there are visible crystals. In this case, there were not any crystals forming on the outside container.

Fowlkes and Lichaj conducted a procedure to neutralize some of the chemicals. The solvents they tested were Xylenes, Cyclopentadienes, and Ethyl Ethers. The test consisted of acetic acid and potassium iodide. They mixed up the solution and added the questionable organic in the solution. A yellow or yellow-brown color is positive, and all of the chemicals except for two turned brown-black.

Fowlkes remembered shaking in that moment and seeing all of the color drain out of Lichaj’s face.

Following the test, Lichaj called Christy Alvear, US Science, Sherri Reed, US Science and department chair, and non-emergency services. He also told Dodson and Fowlkes to go home. The fire department arrived on campus in response, but they were not equipped to handle this situation and proceeded to call the hazmat team. Since the hazmat team was out of their depth, they had to call the bomb squad.

Lichaj gave the bomb squad a list of the chemicals, and they confirmed with the chemists from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). Based on the pictures that they took, the ATF chemists recommended what gear the bomb squad needed to wear. The bomb squad wore minimal protective gear and they removed all of the chemicals by using big buckets of kitty litter and absorbance rocks.

The chemicals were transported to an offsite location and burned. If the chemicals were above a certain concentration, they would have had to cancel the field hockey game (which was going on at the time of the chemical discovery, approximately 4:30 p.m.), construct a burn site in the middle of the field, and detonate the peroxides.

Although this is the first time that has happened at FWCD, this type of situation is something that happens frequently in the world of chemistry.

This type of situation generally occurs when a new teacher takes over.

“Mr. [Shaen] McKnight was an inorganic chemist, so this was sort of out of his realm,” Lichaj said.

These organic peroxides were originally stored by Dr. Jim Aldridge, the predecessor to McKnight and an organic chemist. Since Dr. Aldridge passed away suddenly in 2014, he was not able to tell anyone about the organic peroxides and how dangerous they can become over a long period of time.

In order to assure safety, the chemistry department replaced the acid cabinet and fixed the ventilation system in the stockroom. There is also a professor from Texas Christian University who is consulting on safety.

“It was the best case scenario in a bad situation,” Lichaj said.