Be Bold, Start Cold: Stories from a Summer Camp

Photo Courtesy of Maia Chargois

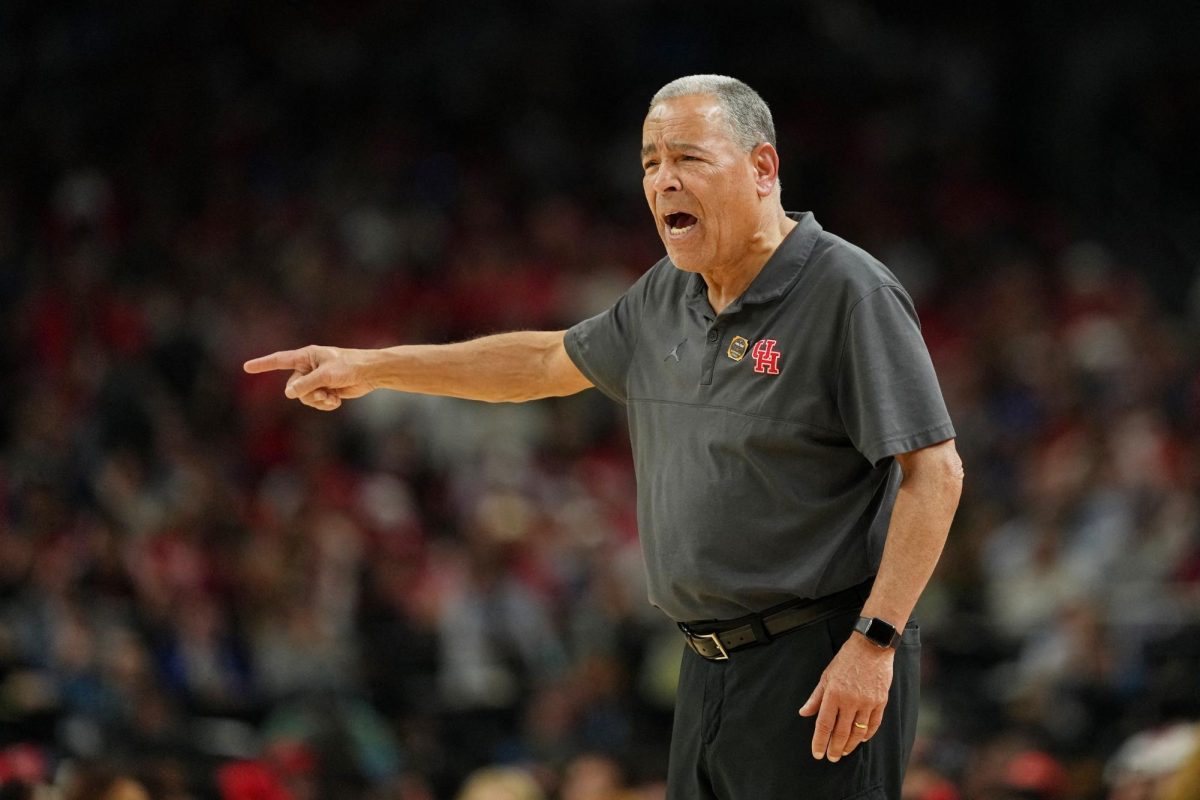

The Zombies take a rest at the peak of Grizz while the sun rises over the distant mountains.

September 6, 2022

This summer, my personal list of “Top Five Stupidest Things I’ve Ever Done” was retooled. One of the new additions to my catalog is climbing a sandwall and navigating a rock field on the side of a mountain, in the pitch black of two in the morning, with no flashlight.

I live my life by one main principle to ensure that I can live, content with myself: don’t be a hypocrite. No matter how hard I try to separate myself from those who inspired me to incorporate that mantra into my life, I still find myself associated with many types of people that make me cringe: die hard Boy Scouts, kids who are more invested in their three-week summer camp lives rather than the ones they have in the real world, and self-proclaimed teenage “writers.” Every time I tell someone about my Eagle Scout rank, I have to quickly follow up the statement with, “No, no, no, I’m not that kind of Scout.”

This past summer was my seventh year at Camp Olympia. Coincidently, it’s also my seventh year of not mentioning that name in public for 351 days out of the year. I always told myself that I didn’t like kids. I’d say that, although I love the time I’ve spent at camp, I could never see myself becoming an employee there. “My tolerance for incompetence runs out pretty fast,” I would tell my dad. Now, I find myself on the path towards becoming a summer camp counselor who gets paid well below minimum wage to receive third-degree sunburns and be harassed by adolescent delinquents.

The whole process to transition from camper to paid employee seems a little wack to me. Your last year as a camper is when you are 15, but the following year, you are blessed with the opportunity to attend the “Camp Leadership Program,” which costs even more than a regular year of camp. What fool would pay to become a paid worker? Me, I guess.

CLP was, in all honesty, an amazing experience which I could never put a price on. Camp Olympia can, however. For the first week and a half, everything that we did, we did wearing hiking boots. When we played kickball, our boots were laced up tight. When we watched Interstellar, our boots never left our feet for the duration of the three-hour film. When we ran two miles then jumped fully clothed into the lake, we were instructed to keep our boots on while we treaded water so that we could empathize with drowning victims. It didn’t help at all that I was outfitted in what I’m pretty sure are the same boots that kept Hitler’s army warm when they attempted to invade Russia in the winter.

The point of wearing our boots every second of the day was so that they would be broken in by the time we reached Colorado. CLP culminates in climbing a mountain, which I guess makes people qualified to be a camp counselor. It’s certainly a trying experience. A three-day backpacking trip means a lot of things that you probably didn’t consider when you signed up for it. For example, defecating in the woods. It’s inevitable that sometime on the mountain, you’ll get the urge for some private time from the chicken enchilada that was for dinner. The problem isn’t the idea of pooping in the wilderness, it’s figuring out how. I was handed a trowel and given the instructions, “Don’t go by the river.” I walked about 200 yards away from the campsite, but I could still hear the muted gabble of my friends over the campfire. For someone who gets nervous using a urinal in stadiums, I knew this was going to be something I wouldn’t want to remember. I spent maybe 20 minutes digging a hole in the ground, then I stood up and stared at it for another 10 minutes, fearing what I would have to do.

I can remember almost everything during my three days on the mountain, but I am so grateful that there is five minutes of darkness in between digging that hole and pulling up my sweatpants, layered over athletic shorts, layered over long underwear. On the walk back towards the basecamp, I looked up to the sky and thanked whatever celestial being had guided me through my journey. It was a spiritual experience. I think I met God.

The next morning, our motley crew of 11 “camp-kids,” a millennial who lives in Los Angeles and does something with social media for a living, and three guides who look like they were pulled from the set of a REI commercial, woke up at two in the morning, so that we could begin our ascent within the next 30 minutes.

I had stupidly left my flashlight in Trinity, Texas, so I began my hike in the pitch black of night. There was no moon, no stars, and no extra flashlight. It was just my luck that within the first five minutes of our walk that morning, we encountered a rock field. I had blindly stumbled over boulders for about 30 minutes before we reached their end, and I was met with a new challenge. For the next hour of the hike, we scaled a near 70-degree sand wall. In all honesty, I had no clue what a sand wall was before I had tried to walk up one. It’s exactly what it sounds like: a wall of sand. For every two steps you take forwards, you end up sliding backwards one step. Rocks would slip out from beneath your feet, crashing down the face of the mountain. When one of these avalanches happened, we were supposed to yell “rocks,” but since I couldn’t see anything, I just closed my eyes and prayed that whatever god had watched me poop was still there.

Once my brain wasn’t using all of its power to make sure I didn’t slide off the side of the mountain, I quickly realized that hiking is an incredibly monotonous activity. It’s just one action, repeated for what seemed to be forever. Left foot, right foot, left foot, and so on. I mean it’s literally one of the two things that zombies can do. The only thing separating us from the undead was that we ate carrots and hummus instead of brains. Everyone just walks in a line, not saying a word, because the air at altitude isn’t enough to satisfy their entitled Texan lungs. My beef jerky supply had been exhausted the previous day on the walk into basecamp, so I had to entertain myself with my own imagination. It’s much worse than it sounds. Regardless, I put my body on autopilot and began thinking. I started off writing this story. I had the first two sentences planned out as you see them now, but then I couldn’t move forward, fearing that I would forget those two Nobel-Prize-deserving sentences. Then, I attempted to remember what the faces of my friends and family look like. I was able to easily capture the looks of my parents, sister, and friends, but I just couldn’t seem to get my dog down. Every time I tried, she ended up looking like Gromit.

Eventually, we got so high in altitude that it hurt to think. Carrying a backpack with enough supplies to sustain a small family for a few months, every step was agony. I’m not an unfit person by any standard, but we all looked like, as Coach Joe Breedlove ‘78 yelled at the middle school basketball D-team, “A train station, with all of our huffin’ and puffin’.” I looked off the edge and imagined throwing my body off the side, quickly recovering from the fall to sprint back to the tent so I could get some rest. Even the rocks below looked like a perfect place for a nap. These feelings didn’t come from a true place of desperation or depression, rather because I had slept for all of three hours in a five-by-six-foot tent which I shared with a TVS student and a sad Rockets fan who wouldn’t shut up about Alpren Şengün, and now found myself freezing in a long sleeve shirt because the guide would robotically repeat, “Be bold, start cold.” Bad advice.

During one of the rest breaks closer to the peak, I stood a little too close to the edge of the mountain. “Hey Marshall, you may not want to stand there,” Maia, the millennial social media worker/camp counselor, told me. “I’m not going to die; I have a different mentality,” I shot back, and thus the phrase “Marshall Mentality” was born. This so-called “Marshall Mentality” isn’t born from optimism, but it encourages a fearless lifestyle where death is no more important than foreign politics are to a redneck.

After four hours of body and mind-numbing walking in pitch black, we reached the peak of Grizz. We approached the top as the sun rose over the distant mountains. The view was quickly spoiled by a passing cloud which trapped us in a heavy fog. We all threw down our packs and collapsed on boulders to rest our legs. Per CLP tradition, Maya handed out frozen Snickers bars to all of the survivors except those with peanut allergies, they received an even colder Honey Bun. We sat, simply exhausted, admiring the view of water vapor as we bit into our chilled candy bars. Sitting at a comfortable 13,281 feet above sea level, we were finally able to look around, catch our breath, and bask in the glory of the accomplishment we had achieved.

The hike back down was rather uneventful, except for a girl named Reese who slipped and fell down the side of the mountain, earning her the nickname “Tumbleweed.” Upon our arrival back at basecamp, through an unspoken agreement, we all climbed into our tents with the intent to hibernate until dinner that night. We awoke a few hours later to rainfall hitting our tents. Everyone had anticipated this by the ominous gray clouds that we had seen in the distance during our descent, so we all brought our boots and backpacks inside the tent. Well, most of us. Reece, the TVS student who slept beside me, had left all of his belongings outside the soaked rainfly. We stood around him as he inspected his drenched possessions. He turned his left boot upside down and a quart of rain water spilled onto the muddy ground. We huddled together for warmth as we sipped hot chocolate from bowls that had held chicken and noodles just a few minutes before. Once again, it was too cold to talk, so I turned to counting to keep myself entertained. I looked down and tallied 10 boots and one pair of very wet socks standing in the quagmire.

Kendall • Sep 6, 2022 at 4:23 pm

might be my favorite story yet